Ukiyo-e Days image

Utamaro Kitagawa was a prominent ukiyo-e artist of the Edo period whose works continue to captivate art lovers in Japan and around the world. Many who search for "Utamaro bijin-ga" are likely drawn to the unique and exquisite portrayal of women in his artworks. In this article, we explore who Utamaro was, and what makes his bijin-ga (pictures of beautiful women) so extraordinary.

Utamaro revolutionized the genre of bijin-ga with an innovative approach. As seen in his famous “Looking-Back Beauty,” he captured not only the expressions and gestures of women but also their emotional nuances, bringing his subjects to life. Unlike mere idealized forms, his women felt real and expressive. Compared with his contemporary Sharaku, Utamaro showed a remarkable talent for discovering beauty in the everyday.

Key Highlights

-

Distinctive characteristics of Utamaro’s bijin-ga compared to other ukiyo-e artists

-

Insights into Utamaro’s personality and artistic career

-

Production background of bijin-ga and the ukiyo-e team structure

-

Utamaro’s multifaceted expressions, including erotic art (shunga)

Contents

- 1 The Allure of Edo-Era Women Captured in Utamaro’s Bijin-ga

- 2 Understanding Utamaro's Art Through a Modern Lens

- 2.1 Who Commissioned Utamaro’s Work?

- 2.2 Team Structure Behind Ukiyo-e Production

- 2.3 What Would Utamaro Be in Modern Times?

- 2.4 If Utamaro Returned in 2025

- 2.5 The Truth About Utamaro's Shunga

- 2.6 Utamaro’s Legacy as a Master of Ukiyo-e

- 2.7 Summary: Innovation and Cultural Significance in Utamaro’s Bijin-ga

- 3 Would You Like to Complete a Bijin-ga in Your Own Colors?

The Allure of Edo-Era Women Captured in Utamaro’s Bijin-ga

Ukiyo-e Days image

ポイント

-

What Makes Utamaro's Bijin-ga Unique

-

Utamaro’s Innovations in Bijin-ga

-

The Ideal Woman Seen Through the Looking-Back Beauty

-

Contrasting Utamaro and Sharaku

-

Who Was Utamaro?

-

Who Commissioned Utamaro’s Work?

What Makes Utamaro's Bijin-ga Unique?

Ukiyo-e Days image

Utamaro's bijin-ga stands apart from those of other ukiyo-e artists due to his distinctive charm. He skillfully depicted subtle emotions through the facial expressions and gestures of women, capturing sensuality and emotional nuances in everyday life.

One of Utamaro’s greatest strengths was his detailed rendering of faces. While many artists of the time idealized facial features, Utamaro gave each woman a unique individuality—highlighting variations in facial contours, eyes, and cheeks—making them appear almost alive.

Another signature technique was his use of “okubi-e” (large-head portraits), where a woman’s face and upper body dominate the canvas. This allowed for deeper expression and more intimate emotional connection with viewers.

Utamaro’s women were never overly flashy. Their clothes and backgrounds exuded elegance and restraint, reflecting the tasteful aesthetic admired by the townspeople of Edo.

At times, his works were deemed too provocative, leading to censorship for violating public morals. Despite this, Utamaro ingeniously maintained dignity while hinting at sensuality—an artistic balance rarely achieved by others.

In essence, Utamaro’s bijin-ga masterfully combined realism with idealism, and sensuality with grace—two seemingly opposite qualities brought together in perfect harmony.

Utamaro’s Innovations in Bijin-ga

Ukiyo-e Days image

Utamaro brought groundbreaking innovation to the genre of bijin-ga. Before his time, portraits of women often focused on external features like hairstyles and kimono patterns, serving more as symbols of beauty than personal expressions.

Utamaro introduced emotion and storytelling into his work. His women smile softly or gaze thoughtfully into the distance, capturing fleeting emotional moments—a radical shift from earlier, more static depictions.

He also incorporated elements of the women’s social lives and daily routines, such as teahouse workers or townsfolk with everyday items. These narrative details made his portraits more relatable and layered.

Visually, Utamaro wasn’t afraid to experiment. He used dramatic lighting, shading, and unconventional cropping techniques to create striking compositions.

While his work sometimes faced censorship, his commitment to new forms of expression earned him lasting respect in art history.

Ultimately, Utamaro’s legacy lies in portraying women not merely as objects of beauty, but as complex, engaging individuals. This set a new standard in bijin-ga that influenced generations to come.

The Ideal Woman Seen Through the Looking-Back Beauty

Ukiyo-e Days image

The term “Looking-Back Beauty” refers to a woman whose backward glance is so graceful it captivates the viewer. This pose became a motif representing the ideal feminine form in ukiyo-e.

Utamaro perfected this style by depicting women from behind, gently glancing over their shoulders. This subtle gesture conveys elegance and mystery, stimulating the viewer’s imagination.

Rather than overtly showing the entire figure, he highlights beauty through restraint—just a glimpse of the face or nape of the neck expresses a quiet sensuality and refinement.

He also showcased contemporary hairstyles and clothing, making his work a visual record of fashion trends during the Edo period. His Looking-Back Beauties symbolized sophistication and urban charm.

By contrast, modern ideals of femininity have evolved. While the Edo era valued modesty and grace, today’s standards emphasize self-expression and independence. In this sense, Utamaro’s work offers a cultural mirror of his time.

Contrasting Utamaro and Sharaku

Ukiyo-e Days image

Both Sharaku and Utamaro are celebrated ukiyo-e artists of the Edo period, but their subjects and artistic approaches diverged greatly. A comparison reveals the unique roles each played in the art world.

Sharaku focused on kabuki actors, capturing theatrical intensity and facial expression through exaggerated realism. He didn’t shy away from depicting wrinkles or distorted features, offering a raw, honest view.

In contrast, Utamaro specialized in bijin-ga, portraying everyday women such as courtesans and townsfolk. His delicate treatment of expression revealed the inner beauty, intellect, and charm of his subjects.

Sharaku minimized background elements to spotlight the subject, while Utamaro used props and settings to enrich the narrative. This reveals Utamaro’s aim to present not just appearance, but also lifestyle and context.

In this way, the artistic contrast between Sharaku and Utamaro showcases the diverse scope and richness of the ukiyo-e tradition.

Who Was Utamaro?

Ukiyo-e Days image

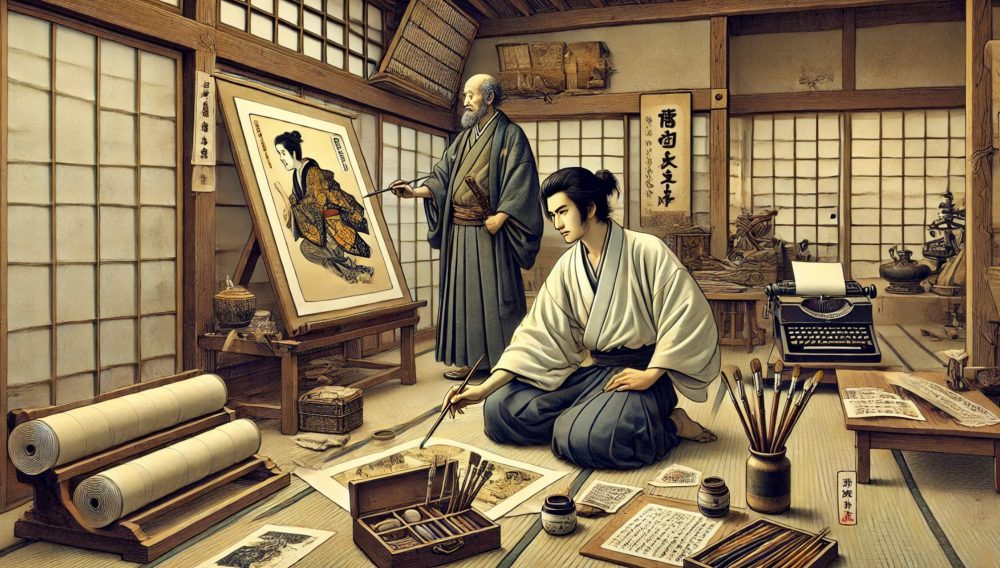

Utamaro Kitagawa was a prominent ukiyo-e artist during the mid-Edo period, known as the foremost master of bijin-ga. His delicate brushwork and refined sensibility won him widespread acclaim, both in his era and today.

Little is known about his early life, but it’s believed he studied under Toriyama Sekien, a painter from the Kanō school. His career took a major turn when he met publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō, who recognized his talent and helped launch him as “Kitagawa Utamaro.”

Unlike many ukiyo-e artists who worked mainly as craftsmen, Utamaro expressed his own artistic vision and emotion through his works—closer to what we might call an “artist” today.

His pursuit of expressive freedom often clashed with government censorship. There were times he was reprimanded or restricted from publishing his works. Nevertheless, his persistence reflected a deep commitment to artistic integrity.

Utamaro did more than depict beauty—he captured the essence of women’s lives and the spirit of the times. Though reportedly quiet and reserved, his art speaks volumes about his passion and perspective.

Understanding Utamaro's Art Through a Modern Lens

Ukiyo-e Days image

-

Who commissioned Utamaro's works?

-

Comparison chart: the ukiyo-e production team

-

Modern-day equivalents of Utamaro’s role

-

If Utamaro arrived in the year 2025

-

Utamaro’s hidden career: the truth behind shunga

-

Utamaro's place as a master of ukiyo-e

Who Commissioned Utamaro’s Work?

Ukiyo-e Days image

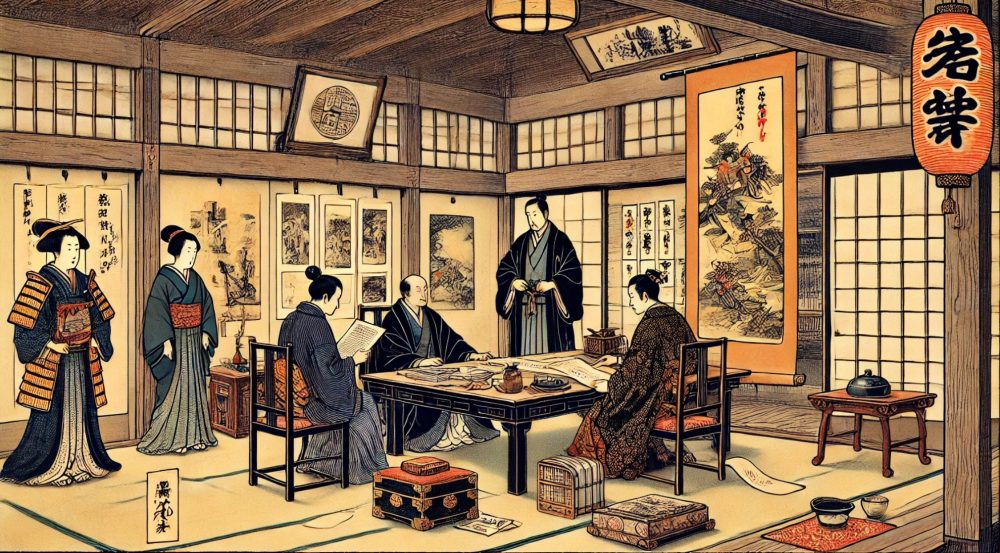

Utamaro’s works were not created spontaneously or for personal interest. Instead, they were commissioned by publishers known as “hanmoto.” These figures functioned like modern producers or editors, overseeing both business and creative aspects.

Ukiyo-e production was a collaborative process involving the artist, carver, and printer—all organized by the publisher. The hanmoto would research market demand and direct artists with themes expected to sell well.

One of the most famous was Tsutaya Jūzaburō. He discovered Utamaro early on and commissioned numerous bijin-ga and shunga works. Tsutaya even provided Utamaro with housing to support his creative efforts.

Because of government censorship, publishers had to navigate legal risks. If content was deemed morally disruptive, they could face punishment. Trust between artist and publisher was essential under such constraints.

Utamaro’s work was shaped not just by personal expression, but also by commercial demand and cultural trends—making it a collaborative enterprise more than solitary art.

Team Structure Behind Ukiyo-e Production

Ukiyo-e Days image

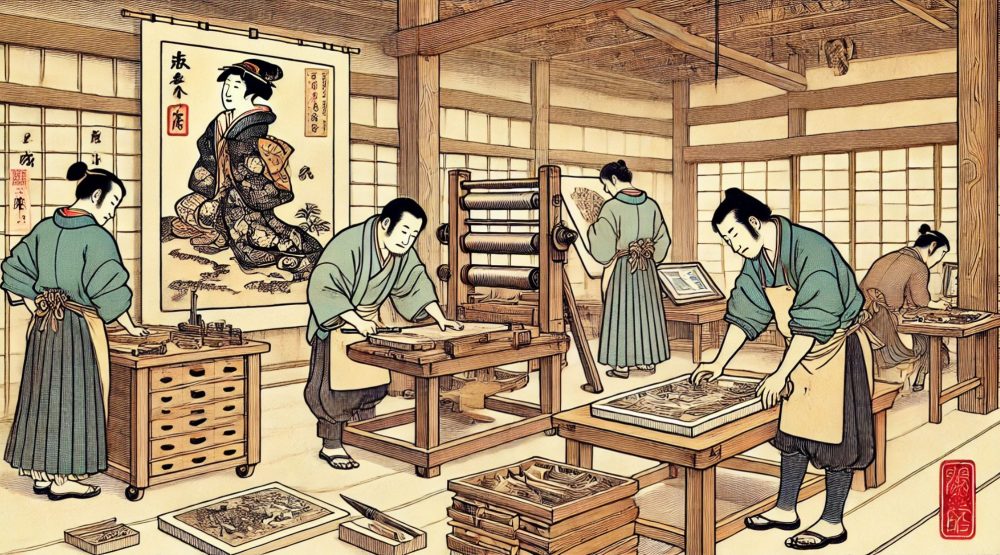

Creating ukiyo-e prints required a highly collaborative team. Much like today’s editorial or design projects, each role was clearly defined:

| Ukiyo-e Role | Modern Equivalent | Main Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Artist (Eshi) | Art Director / Illustrator | Creates the original sketch and overall visual concept |

| Carver (Horishi) | Graphic Technician / Woodcarver | Carves the sketch into wooden printing blocks |

| Printer (Surishi) | Print Operator / Production Technician | Applies ink to blocks and prints onto paper, often in multiple layers |

| Publisher (Hanmoto) | Editor / Producer | Manages planning, funding, sales, and overall production |

Ukiyo-e was not just an art form—it was a sophisticated commercial system. Often, the artist would supervise the first prints, guiding color tones and line work to ensure accuracy and artistic quality.

Today, people often credit the final piece solely to the artist. But in truth, it was the result of meticulous collaboration among skilled craftsmen. This team structure was key to the enduring success of ukiyo-e.

What Would Utamaro Be in Modern Times?

Ukiyo-e Days image

If we were to compare Utamaro’s role to a modern profession, he would be akin to an advertising creative or a fashion magazine art director. He didn’t merely draw pictures—he visualized society’s ideals of beauty and stirred the desires and emotions of the public.

In the Edo period, bijin-ga functioned much like today’s fashion photography or visual branding. Every element—from hairstyles to facial expressions and kimono patterns—was carefully composed to reflect contemporary trends.

Utamaro also acted as a trend-setter. Working closely with his publisher, he curated and produced themed series, including erotic works, much like a modern visual content strategist or art book producer. Through these efforts, he launched visual icons and cultivated public admiration.

In this sense, Utamaro was not just a craftsman but a visionary who shaped the aesthetic direction of Edo society through strategic visual storytelling.

If Utamaro Returned in 2025

Ukiyo-e Days image

If Utamaro were to appear in 2025, he would likely thrive in today’s diverse and digitally connected creative world. His innovative spirit and commitment to expression would make him a leading figure in contemporary art scenes.

With today’s visual tools and platforms—like social media, digital art, and inclusive cultural movements—Utamaro would find new ways to explore themes of beauty, identity, and gender. He might use Instagram as a gallery, or direct campaigns exploring body positivity and gender fluidity.

His experience with shunga also suggests he’d challenge modern taboos around sexuality, becoming a bold and progressive voice in feminist or queer art discourse.

Of course, he might encounter issues around copyright or compliance, but it’s easy to imagine him cleverly subverting those systems—just as he navigated censorship in Edo Japan.

Utamaro would undoubtedly express themes of beauty, sensuality, and freedom with sharp insight and striking visuals in today’s world.

The Truth About Utamaro's Shunga

Ukiyo-e Days image

Though best known for bijin-ga, Utamaro also produced many works of shunga—erotic art that was widely popular in the Edo period. Far from being simply explicit, shunga was a respected genre full of wit, aesthetics, and social commentary.

Shunga, also known as “pillow pictures” or “laughing pictures,” was enjoyed by both men and women. Utamaro’s work stood out for its artistic quality—his use of composition, linework, and expression elevated shunga to a sophisticated art form.

However, shunga carried significant risk. The Tokugawa government periodically enforced strict moral codes, and Utamaro himself faced penalties for publishing erotic works deemed too provocative.

Yet his treatment of sexuality was progressive. Rather than hide it, he portrayed it with humor and humanity. In doing so, Utamaro captured the openness and earthy joy of Edo’s sexual culture—a far cry from shame-based attitudes in other eras.

Ultimately, his shunga was not just an underground venture—it was a powerful form of self-expression and cultural reflection, contributing greatly to the richness of ukiyo-e art.

Utamaro’s Legacy as a Master of Ukiyo-e

Ukiyo-e Days image

Utamaro holds an unshakable position in the history of ukiyo-e as the definitive master of bijin-ga. His work transformed the way women were depicted in Japanese art.

Previously, bijin-ga relied on stereotypical beauty standards. But Utamaro added individuality and emotional depth, making his subjects feel human and relatable. His use of close-up portraits (“okubi-e”) was especially innovative, capturing expressions with unprecedented intimacy.

Working with publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō, Utamaro balanced artistic excellence with widespread appeal. His portraits of courtesans and townspeople reflected real trends, lifestyles, and the mood of Edo society.

However, his bold style didn’t always sit well with authorities. Later in life, he was censured for disrupting public morals, limiting his ability to publish. Yet his influence continued to shape ukiyo-e, inspiring future generations of artists.

Today, Utamaro’s works are celebrated in museums around the world as icons of Japanese culture. More than a fashionable illustrator, he was a true artist of rare sensitivity and technical brilliance—an enduring master of his craft.

Summary: Innovation and Cultural Significance in Utamaro’s Bijin-ga

- Utamaro’s bijin-ga delicately expressed women’s individuality and emotion

- His close-up portraits (okubi-e) highlighted facial expressions like never before

- He used understated attire and backgrounds to convey graceful sensuality

- He pioneered emotional and narrative expression in bijin-ga

- He captured everyday life—like teahouse workers and town girls—with realism

- His role is comparable to a modern art director or fashion visual strategist

- Publisher Tsutaya Jūzaburō played a key role in supporting his work

- His bijin-ga reflected the aspirations and trends of Edo townspeople

- His “looking-back beauties” embodied ideal femininity with subtle allure

- Unlike Sharaku, Utamaro emphasized everyday beauty and inner expression

- Ukiyo-e production was a team effort among artists, carvers, printers, and publishers

- Utamaro often oversaw first prints to ensure quality and detail

- His shunga also displayed exceptional artistry and expressive power

- His pursuit of artistic freedom led to clashes with Edo-era censorship

- He is remembered as a master who shaped ukiyo-e for future generations

Would You Like to Complete a Bijin-ga in Your Own Colors?

Want to experience the true charm of bijin-ga up close?

We’ve created an adult coloring activity inspired by Utamaro’s work.

Bring Edo-era aesthetics to life with your own modern touch.